How To Increase Savings Rate In An Economy

The implications of savings accumulated during the pandemic for the global economic outlook

Published as office of the ECB Economical Message, Issue 5/2021.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has led to the accumulation of a big stock of household savings across avant-garde economies, significantly to a higher place what has historically been observed. Owing to their large size, the savings accumulated since early on 2022 have the potential to shape the mail service-pandemic recovery. The key question is whether households volition spend heavily once pandemic-related restrictions are lifted and consumer confidence returns, or whether other motives (e.thou. precautionary, deleveraging) volition keep households from spending their accumulated backlog savings. In this box nosotros consider a prepare of non-euro area economies and conclude that, on the balance of economical arguments, any reduction in the stock of backlog savings as a result of college consumption is likely to be express in the medium term. However, given the considerable uncertainty surrounding this cardinal scenario, this box besides looks at two culling savings scenarios and assesses their implications for the global economical outlook using the Oxford Global Economical Model.

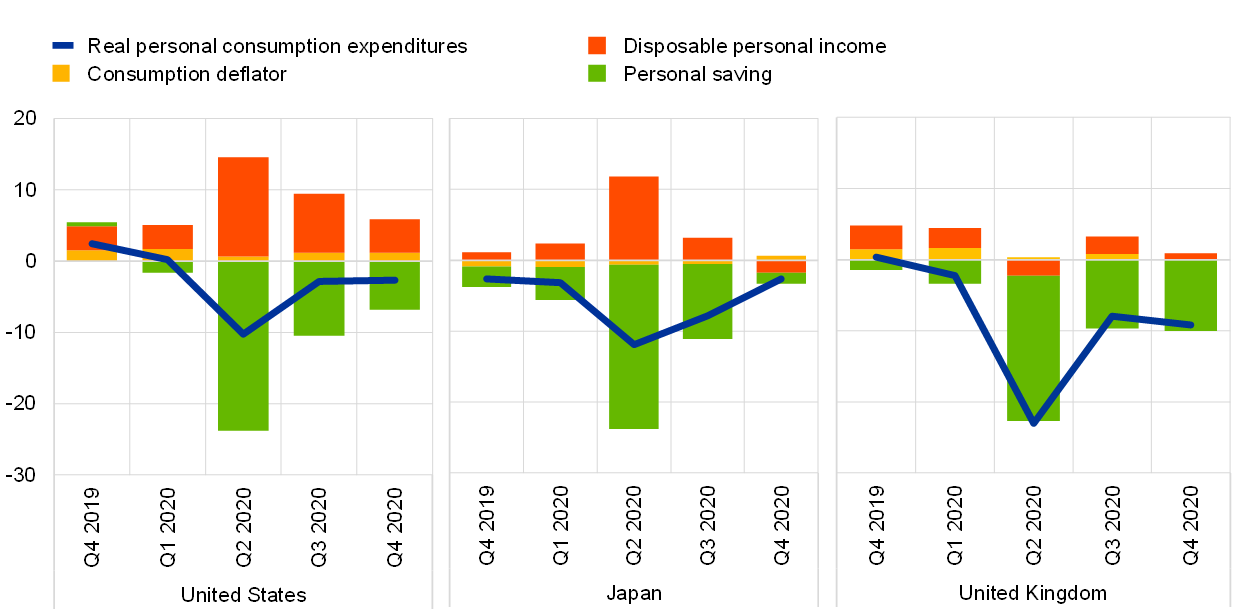

The accumulation of large savings stems from the distinctive features of the COVID-nineteen pandemic and the policy responses. In contrast to previous economic recessions, the containment measures adopted in response to COVID-19 saw a significant suppression of consumer spending opportunities, leading to a sizeable contraction in private consumption. This was partially outset past the extraordinary policy measures deployed by governments in the class of either income or employment support, which cushioned the negative impact on personal dispensable income (Nautical chart A, panel a). These two factors, together with the high incertitude regarding hereafter income and the risks of permanent scarring effects, led households to salve at unprecedented rates during 2022, resulting in the aggregating of a large stock of excess savings.

In 2022, the stock of household savings accumulated across five large avant-garde economies [1] in excess of historical values amounted to an average of six.7 % of GDP and 9.v% of disposable income (Chart A, panel b). Of these countries, the United States held the largest stock at the finish of 2022 (USD 1.5 trillion, or 7.2% of The states Gross domestic product), but other countries likewise held sizeable amounts of excess savings. The stock of excess savings accumulated between early 2022 and the end of the year is estimated past calculating the cumulative difference betwixt real savings and a counterfactual scenario where the saving ratio is causeless to have remained equal to the pre-pandemic average throughout the year. Similarly, our central scenario assumes that, upwards to the end of 2023, the stock of backlog savings remains close to the level observed prior to the start of 2022, while the saving ratio is assumed to converge back to the pre-pandemic average.

Chart A

Private final consumption expenditure and excess household savings

a) Private final consumption expenditure breakdown

(annual percentage modify, percent points)

b) Excess household savings in the fourth quarter of 2022

(percentages)

Sources: National sources and ECB calculations.

Notes: The advanced economies (AE) aggregate is calculated as the weighted average of excess savings beyond the five countries shown in the chart. "Usa" refers to the Us, "UK" to the United Kingdom, "JP" to Japan, "CA" to Canada and "AU" to Commonwealth of australia.

Several arguments support the central scenario that households volition prefer to concord nigh of their accumulated excess savings rather than using them to purchase consumption goods. We review these arguments briefly below, before illustrating the macroeconomic implications of two alternative savings scenarios.

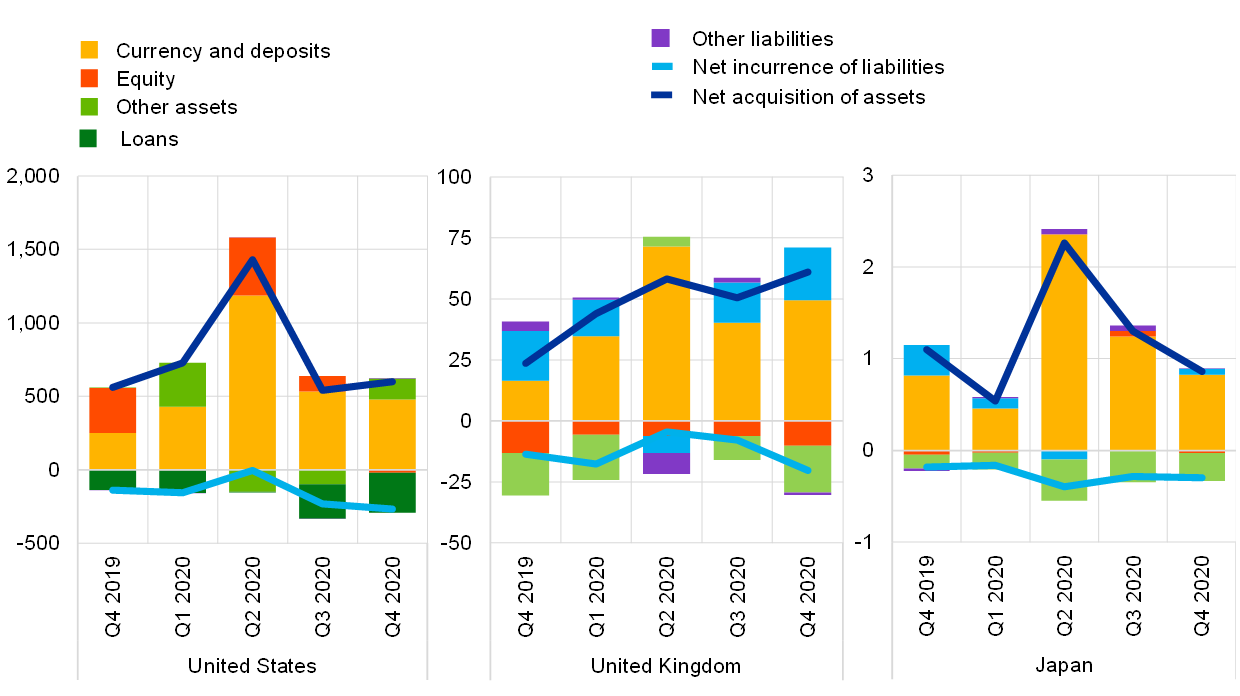

First, the savings accumulated during the pandemic accept mostly accrued to high-income households, who have a lower marginal propensity to spend out of income or wealth compared with low-income households. [ii] In the United Kingdom, for instance, survey-based data bear witness that high-income households increased their savings during the pandemic, while lower and centre-income households saved less or even dissaved. Similarly, in the United States there is evidence that the distribution of backlog savings across income groups is heavily skewed in favour of loftier-income households and that these savings are held by and large in liquid form, i.due east. currency and deposits (Nautical chart B, both panels). A similar situation holds in the euro area, where the accumulation of savings during the pandemic has been concentrated among older and higher-income households (for details, see Box 4 in this upshot of the Economical Bulletin). In Nihon, available information too suggest that savings have accumulated mainly among middle and high-income households. In full general, high-income households are likely to accept saved more during the pandemic, equally they experienced lower income losses than depression-income households and tend to allocate a higher share of their consumption basket to the services that were most constrained during the lockdowns. For instance, available data indicate that, before the pandemic, UK households in the top income decile devoted close to 40% of their expenditures to services such as transportation, recreation, hotels and restaurants.[iii]

Chart B

Financial assets and liabilities of households

a) U.s.a. checkable deposits and currency across income quintiles

(USD trillions; percentiles)

b) Financial avails and liabilities of households

(USD billions; GBP billions; JPY trillions)

Sources: United states of america Federal Reserve System (panel a); national sources and ECB calculations (console b).

Second, households may utilize part of their accumulated savings to repay debt or to invest in avails. With regard to financial accounts, the accumulation of large savings has been associated with a surge in household depository financial institution deposits during the lockdowns. Prior to the end of 2022 only a small proportion of these savings had been used to repay debt or purchase assets such as equities (Chart B, panel b). This liquidity preference could partly reflect high uncertainty amongst households, in add-on to reduced availability of consumption opportunities amid persisting COVID-19-related restrictions. As uncertainty recedes, a larger proportion of savings could be channelled towards investments or debt repayment. In the United states, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York'due south Survey of Consumer Expectations suggested that almost of the funds received by households in the course of stimulus cheques would go towards savings (41%) and debt payments (34%), while only about 25% would be used for consumption.[iv] In the Great britain, the 2022 H2 NMG Survey suggested that only 10% of households whose savings rose planned to spend them, while 70% favoured continuing to hold their savings in banking company accounts.[5] The remainder planned to use their savings to pay off debts, invest or height upwardly their retirement plans.

3rd, Ricardian equivalence furnishings may weigh on households' propensity to swallow, all else being equal. [half dozen] The considerable income back up provided to households and other policy measures taken during the pandemic led to a strong dissaving in the public sector and an associated increase in public debt. In the future, Ricardian equivalence effects may arise, to the extent that households wait tax rises aimed at reducing the public debt accrued during the COVID-19 stupor and are thus less inclined to swallow their accumulated excess savings. In this regard, it is worth noting that both the US Regime and the UK Government have announced personal income taxation increases, which are expected to weigh on households' propensity to consume.

Fourth, the scope for sizable pent-up demand appears express. While the easing of mobility restrictions and the progressive reopening of contact-intensive sectors volition save household demand for consumption of related services (east.g. travel, restaurants and cultural activities), the latter are less decumbent than consumption goods to massive bouts of pent-up demand.[7] In item, while consumers might have an incentive to switch to more than expensive services (due east.one thousand. holidays and restaurants), there is a limit on the extent to which they tin can catch up in terms of missed consumption. In add-on, as the pandemic-related containment measures severely express consumption opportunities in the services sector, part of household spending switched towards consumption of appurtenances. Data on existent personal consumption expenditures of US households bear witness that spending on durable and non-durable appurtenances bounced back quickly after falling considerably in Apr 2022; by the end of the second quarter of 2022, overall spending had returned to the levels observed at the end of 2022 and has subsequently continued to grow. Expenditures on services, while recovering at a slower stride, stood at effectually 5% beneath pre-pandemic levels by March 2022.

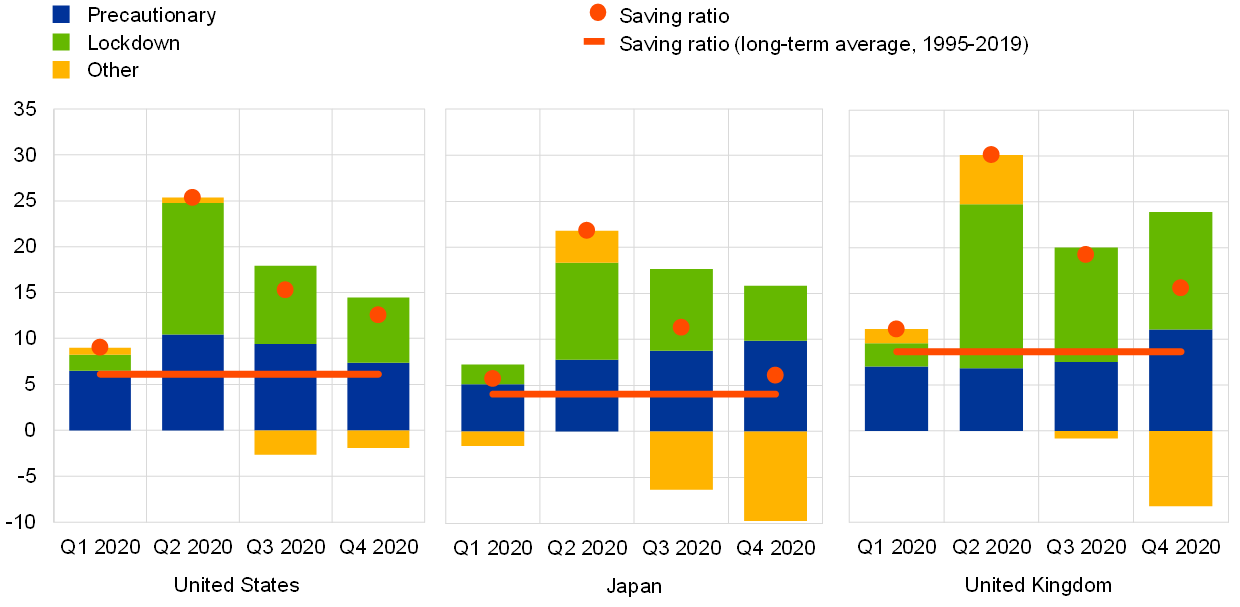

Notwithstanding, uncertainty effectually the relative forcefulness of the factors that could influence how much of the accumulated savings is spent remains high. On the i paw, a gradual but lasting re-opening of economies, as the pandemic is brought nether control, would lead households to de-accumulate savings at a faster step than assumed in our central scenario, reflecting the fact that these savings were forced to a certain extent as the response to the pandemic curtailed consumption opportunities. Beingness held mostly in liquid assets, savings could exist spent very hands. The resumption of contact-intensive activities such as shopping and dining will restore spending opportunities that were previously unavailable, in particular for high-income households that devote a larger share of their consumption basket to such activities. Moreover, as the recovery progresses and employment prospects amend, precautionary motives for saving, which played an important role in 2022, may too go less relevant as households regain conviction about their economic and health prospects (Chart C). On the other hand, setbacks in bringing the virus under command, prolonged restrictions, new lockdown measures and weaker labour marketplace prospects could atomic number 82 households to further accumulate savings, compared with the central scenario, and thus delay the recovery.

Chart C

Breakup of household savings by motive

(percentages of disposable income and percentage points contribution)

Sources: National sources and ECB calculations.

Notes: The analysis covers the period from the first quarter of 1995 to the fourth quarter of 2022. The ratio of household savings to disposable income in 2022 (carmine dots) is modelled in an ordinary to the lowest degree squares (OLS) framework and is expressed equally a office of its own lag, the unemployment rate, economical confidence and country-specific lockdown measures, equally captured by the Goldman Sachs Constructive Lockdown Index.

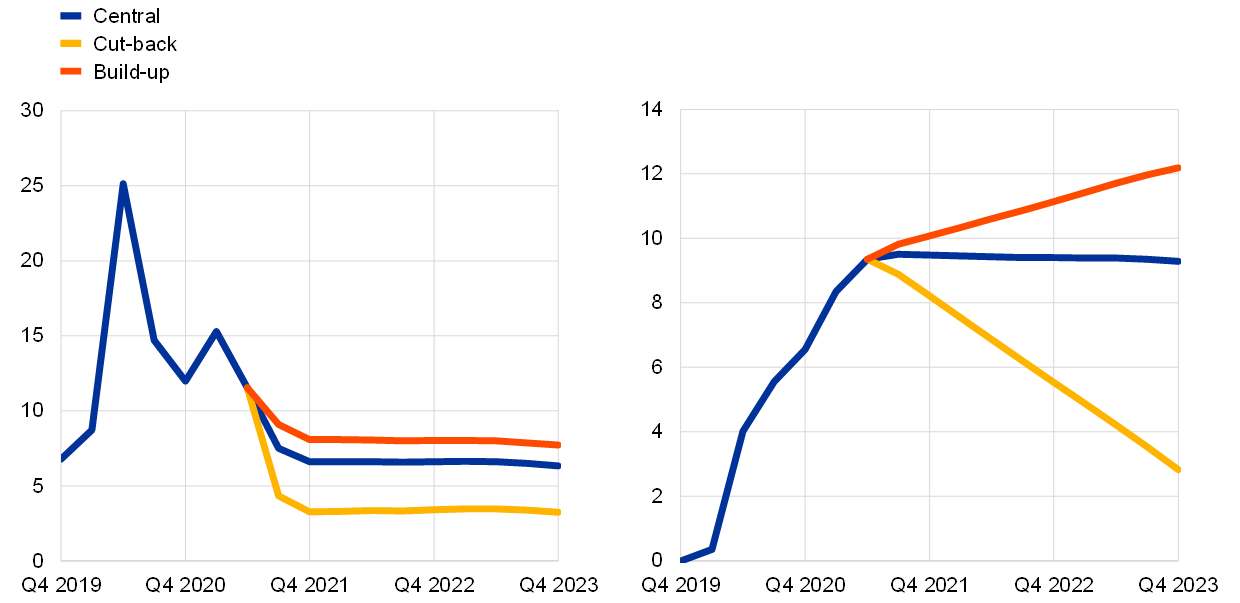

Chart D

Scenario projections for the household saving ratio and stock of backlog household savings

(percentages of disposable income (left console); percentages of Gross domestic product (correct panel))

Sources: ECB calculations based on the Oxford Global Economic Model.

Note: Results are aggregated using weighted Gdp.

To assess the macroeconomic implications of alternative savings scenarios for the Us, the United Kingdom and Nihon, we consider two alternative scenarios[eight] for the stock of backlog savings. These are (i) a "cutting-back" scenario, which assumes that the stock of excess savings accumulated by the second quarter of 2022 will decrease by 70% over the next two and a half years, and (ii) a "build-up" scenario, which assumes that the saving ratio will return to pre-pandemic levels only in the 4th quarter of 2023, implying that households volition increment their current excess savings by a further xxx%. As a result, boilerplate excess savings in these economies would decline to 2.7% of GDP in the cutting-dorsum scenario and increase to 12.half-dozen% of Gross domestic product in the build-upwardly scenario by the end of 2023 (Chart D). Nosotros employ the Oxford Global Economical Model to quantify the effects of the two scenarios on the global macroeconomic outlook.[nine]

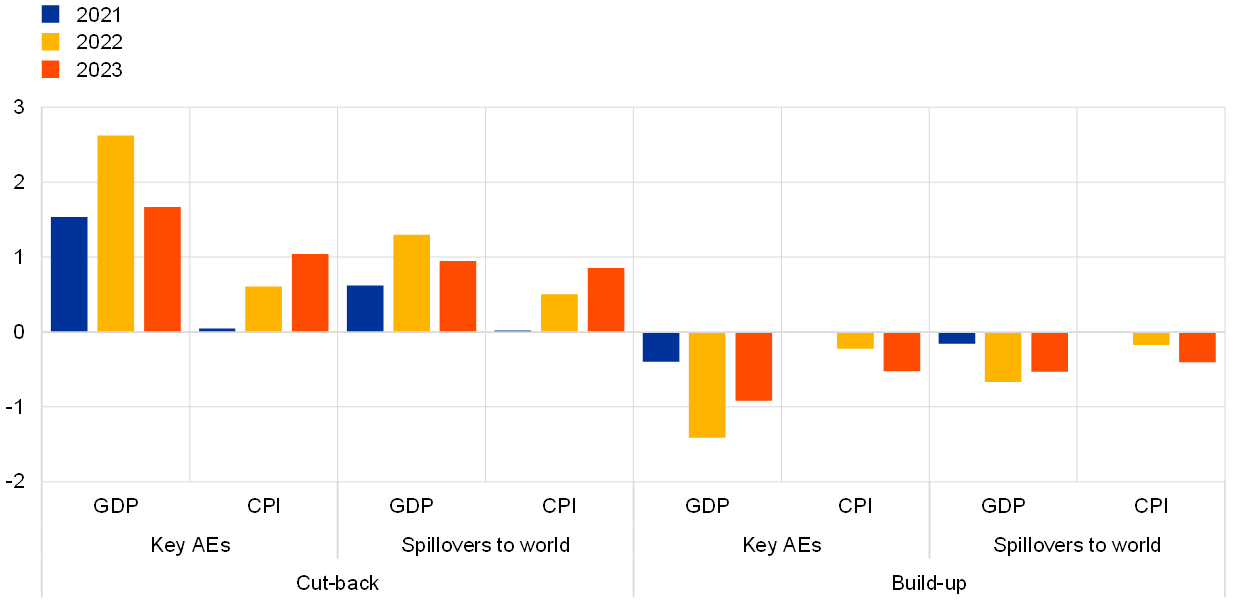

Chart East

Macroeconomic impact of alternative household savings scenarios on GDP and CPI in the "cut-back" and "build-upwardly" scenarios

(percentage deviation from primal scenario level)

Sources: ECB calculations based on the Oxford Global Economic Model.

Notes: The affect on GDP and CPI in key advanced economies (AEs) is the Gross domestic product-weighted boilerplate impact across the U.s.a., the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Japan; spillovers are assessed using the Oxford Global Economic Model, where "world" refers to the global economy, including the U.s.a., the Britain and Nihon.

In the cut-back scenario, the faster reduction of savings in the form of higher private consumption supports aggregate demand and a choice-up of aggrandizement. In key advanced economies, existent GDP is projected to peak at 2.half-dozen% higher up the central scenario level in 2022 (Chart East). This positive boost would be partly counteracted in 2023 by stronger imports condign a drag on GDP. The increase in aggregate demand would also back up price pressures, which would gradually increase over the projection horizon and translate into higher inflation rates (1% above the key scenario level in 2023). The global impact would be significant, with earth real Gross domestic product continuing at 0.half-dozen% above the central scenario level in 2022, 1.iii% in a higher place in 2022 and around 1% to a higher place in 2023. Global inflation would likewise increase, with consumer prices rising to around 0.nine% above the central scenario level in 2023, supported by global demand conditions.

In the build-up scenario, households go along to accumulate savings, resulting in a more subdued pick-up in private consumption, a delayed recovery and express disinflationary pressures. Continued high savings by households over a longer period would translate into lower amass demand and inflation. Domestic GDP would therefore recover more slowly than causeless in the cardinal scenario and world Gdp would stand at 0.2% below the key scenario level in 2022, 0.7% below in 2022 and around 0.5% beneath in 2023 (Chart E). The impact on global inflation would be limited. It is worth noting that despite the downside risks to global output, the build-up of household savings may yield longer-term gains in terms of stronger household balance sheets (eastward.grand. lower leverage) to withstand time to come adverse shocks.

The analysis presented in this box illustrates the risks to global Gross domestic product in different household savings scenarios. The extent to which households across advanced economies will spend excess savings on consumption goods is crucial for the global outlook and is tied to several factors, not least the evolution of the pandemic (including progress in domestic vaccination campaigns), households' employment prospects (especially for those with more modest income levels) and expected financial policy stances.

Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2021/html/ecb.ebbox202105_01~f40b8968cd.en.html

0 Response to "How To Increase Savings Rate In An Economy"

Post a Comment